The Post Office

"The building has long been an economically and socially significant part of the local community"

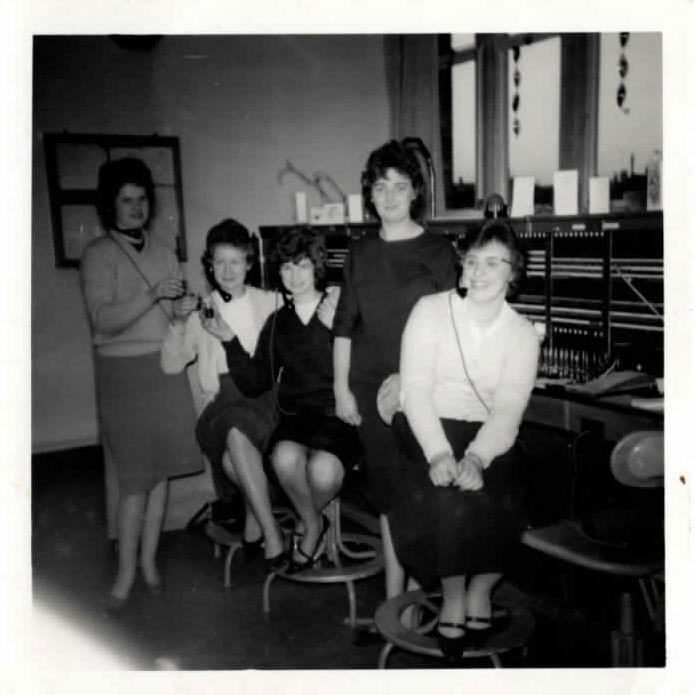

The building has long been an economically and socially significant part of the local community; many Saxmundham residents worked in the telephone exchange, which at its height employed around fifty people.

However, as the hardware of technology decreased in size, and the need for people manning the exchange was surpassed by new digital technologies, large areas of the building became disused and its role became unclear. In early 2020, The Art Station took over the first floor of the building, renovating and repurposing it as a creative space: creative workspaces, a project space, tech space – to support the development of the creative industries in coastal Suffolk, as well as enabling new networks to develop in the region.

To delve further into this incredible history at the heart of Saxmundham, oral historian Belinda Moore interviewed former employees of the telephone exchange, to capture and immortalise their stories.

Barbara Ball

"I had to go through more training to get everything right, to learn to say things correctly."

Barbara Ball, 91, lives in Friston. She worked as a telephone operator in Saxmundham and Ipswich throughout different periods from the 1950s to 1980s.

She left school at the age of 14 and went to work first as a nanny for a family in Rendham, and then moved to work for a Lady Sinclaire. Her work as a nanny for Lady Sinclaire took her to Scotland, Malta and Cyprus.

When she came back to Saxmundham, both her brother and father worked for the Post Office – she saw an advert there for a Telephone Operator in Saxmundham High Street. Alongside the other trainees, she was sent to the telephone exchange in Aldershot for initial training on the switchboard as well as to learn how to speak in the proper manner for the role.

Barbara worked at Saxmundham Telephone Exchange until 1956, when her first daughter was born. After the birth of her daughter, her family moved to first to Ipswich, and then to Kesgrave, where she worked at the BT exchange there in the evenings.

In 1965, there was a migration scheme initiated by the governments of Australia and New Zealand colloquially called “£10 poms”. Her family (her husband and two daughters) emigrated to Australia thanks to the scheme. They lived in Australia for 5 years, before deciding to move back to England, where she resumed work as a Telephone Exchange Operator in Saxmundham. Her husband, a Mr. Kemp, was sadly killed in a traffic accident in the early 1980s. Barbara was later remarried in 1986, though retired from work (at the Ipswich exchange) in 1987.

Interview: Barbara Ball

You were telling me that you were at home in Saxmundham, that both you and your dad were working for the Post Office when you saw an advertisement for a Telephone Operator and you decided to give that a go. You were about 18, I think?

Yes, about 18 or 19. I’d just come back from looking after children in Cyprus and Malta, and I thought it was about time to settle down in Saxmundham. So, I applied for the job. At the time I didn’t even know where the telephone exchange was, but I got the job. So, then I had to wait until they sent me off to Aldershot for a fortnight for training. That was a bit of an eye opener. I walked into the telephone exchange in Aldershot and it was a bit noisy you know – lots of lights flashing and people chatting. Anyway, for the training we had to go to a little sub-post office outside of Aldershot. There were two switchboards in their back room. Myself and another girl who was also training had to use these little boards. It was all a bit unnerving to start with because we didn’t know if we were going to cut anybody off, or pull out the right plugs. It was a bit worrying but we got through it. And after a while we passed and I came back to Saxmundham.

Andrew Nunn

"It was a lot of responsibility. You have to remember that health and safety wasn’t quite as strict as it is now."

Andrew Nunn, from Leiston, worked as an engineer based at the Aldeburgh Repeater Station from 1970-1980 and used to come to Saxmundham Telephone Exchange to carry out maintenance and provide co-operation if required.

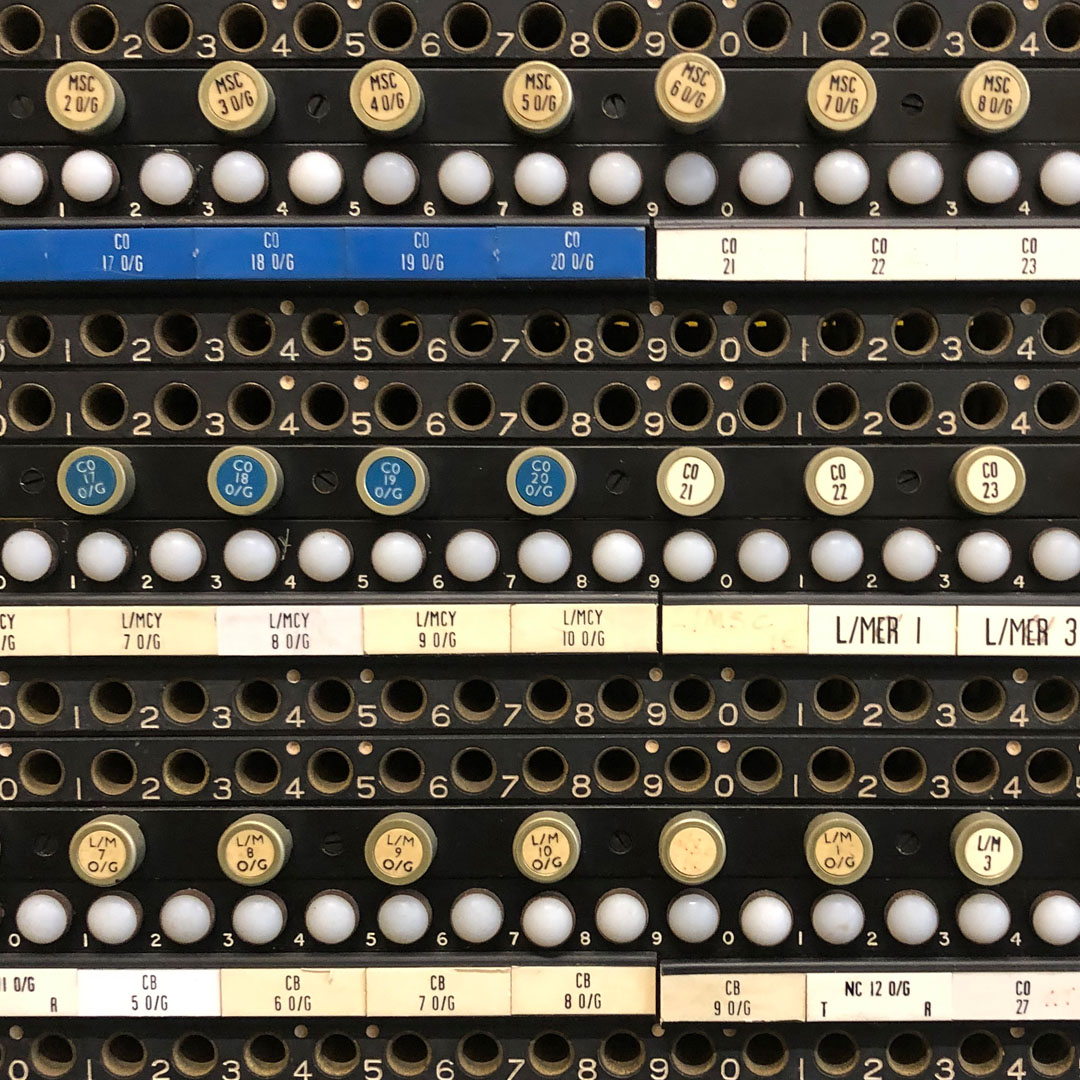

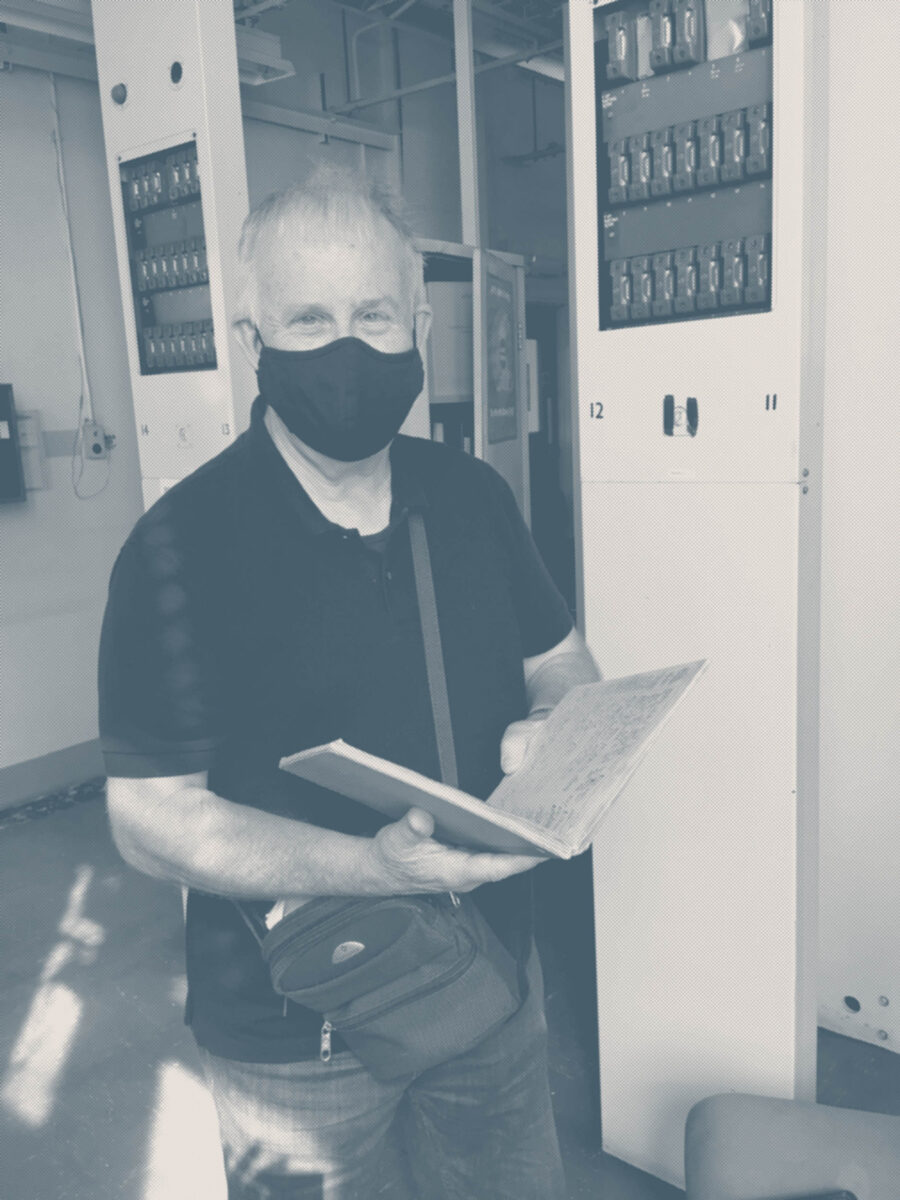

The Repeater Station within Saxmundham Telephone Exchange is the part on the ground floor with cream-coloured equipment tracks. It was open to the public on 18th September 2021

Interview: Andrew Nunn

Once we got the lid off the foot way box––which some may call a man hole––but it was a foot way box, which was shallow as opposed to the deeper ones. We’d take the top off and we could plug our socket on the side with the rubber cap on, plug our speaker box in there, and then we could talk back to the person left in the station. You could talk both ways and we’d say “right, we’re here now” and we’d start looking [for the problem]. [The caps] were pressurised to stop water getting in, so we’d have to depressurise them with an ordinary car valve, unscrew it, take it out, and put it somewhere safe so you didn’t lose it. Once it was depressurised––we checked it was depressurised with the gage––you could then undo some clamps and take the lid off and then you could actually see all the equipment inside the box.

Three staff at Aldeburgh provided maintenance cover 24/7/365. I remember frequently travelling from my home in Leiston to Saxmundham in the middle of the night on very icy roads or in thick fog. We were called out by the Telephone Operators working on the switchboard at Saxmundham. It was usually male operators that covered the night shift. I enjoyed working with the other staff in the switching part of the Telephone Exchange, including the Operators. I experienced very good co-operation from the staff there. The Post Office was just like one big family where we all looked after one another.

We looked after Saxmundham, and we were also responsible for finding faults along the road. What would happen was that an alarm would come up, and you’d have the means of locating where it was, and you’d say it’s an ‘amplifier point six’ or something on the map. Then you’d see that’s outside number three somewhere so you’d load the van up, well actually we didn’t have a van in those days, we had a car, so we’d put it all in a car. We’d load all our stuff into the boot of the car and off we’d go.

Yes, there was a lot of that going on. I can’t think of any specific examples at the moment but it was always part of the job. There was lots of leg pulling, lots of quite elaborate practical jokes, and looking back on some of them, you think some of them were actually a bit childish but it was a different time. Things have changed an awful lot; people expect a lot more now.

This one dreadful thing happened, though. Where the internal cables pass between floors there was a hole cut in the floor and it was a nice neat hole lined with mahogany usually. Cables would pass through, but of course you had to make sure fire couldn’t get through there, so the holes would have a board on the bottom and a board on the top and packed with little bags of asbestos. Nobody knew asbestos was dangerous in those days, so there used to be loads of these bags. Inevitably you’d be walking through the exchange and you’d get one around the back of the head because people would have what essentially was snowball fights with them. It was quite normal back then but of course we wouldn’t dream of it today. Well, we wouldn’t have dreamt of it back then if we’d known it was actually dangerous. We thought asbestos was perfectly safe because it was everywhere.

Dennis Chilvers

Former BT Engineer

David Rowland

"One of the tasks to be undertaken on a routine basis was to measure the specific gravity of the electrolyte"

David Rowland is a former engineer who worked at Saxmundham Telephone Exchange at various times throughout his long career with BT.

Interview: David Rowland

I worked at Saxmundham Telephone Exchange at various times during my career with BT (formerly Post-Office Telephones) between 1973 and 1988. During my apprenticeship, I had a stint in the auto (short for automatic exchange) learning how the electromechanical switching systems worked, as well as the maintenance needed to keep things working in tip-top condition. Colleagues leading me through this were Peter Foster, Trevor Mayhew and Derek Whiting. The test desk was staffed by David Last, who was a great help when I was working as a line man fixing customer (then called ‘subscribers’) phone faults. The AEE (Assistant Executive Engineer) in charge was initially Ray Boggis, who was succeeded by John Barker. The manual board staffed by Operators on the first floor was a place of intimidation to a teenager; the Operators had a wicked sense of humour when their supervisor wasn’t around.

The noise of the switching equipment was very distinctive, and it was strange to walk back into the building and find it silent, with all the electromechanical equipment removed. It’s a shame that we were not granted access to the power and battery rooms, or to the equipment area on the first floor. The Strowger (electromechanical) equipment was powered by 50VDC from large open cells in the battery room. One of the tasks to be undertaken on a routine basis was to measure the specific gravity of the electrolyte, and add distilled water to the cells to maintain this within correct operating limits.

Occasionally, test discharges were required to ensure the battery was capable of maintaining the exchange during power failure conditions. An engine set was available to provide mains power to the exchange in case of an external power outage. There were diesel tanks under the back yard that were kept topped up and offered around 30 days of operating capacity. The Strowger equipment required a degree of preventative and reactive maintenance to keep operating.

There were a number of automated routine tests that were run overnight to test the various switches and relay sets printing out pink dockets with fault details as appropriate. One of my tasks was to go through these fault dockets every morning and resolve any issues found. If it was not possible to quickly fix the switch, a link was moved to “busy” so it would not be selected by the exchange when calls were being made/received. The switch could then be worked on during the day and restored to service once the fault had been resolved. Throughout the day, various alarms would sound and available engineers would be directed to the alarm location via the lantern stack. There were a number of these located throughout the exchange at strategic locations. Alarms were coded by both colour and letter/number combinations. Power alarms were blue, major alarms were red, and non-urgent were yellow or white.

Each suite line was fitted with red and yellow lamps which lit up when a fault occurred in that suite. Similarly, each rack within the suite was fitted with red and yellow lamps to allow engineers to quickly see where issues were present within the suite. In addition to the telephone exchange, there was an associated repeater station that provided the connectivity to adjacent switching centres and also housed equipment that serviced private wires and telex services. Much of the equipment racks of the repeater station are still present at Saxmundham. These are all 62 type racks typified by their light straw colour. I was pleased to find entries I had made in the repeater station log book, as well as the trunk services directory (THQ3210) that were still present.

When I finished my apprenticeship in 1976, I was to be deployed into the exchange on maintenance activities. From all the various departments and work areas that I had experienced during my apprenticeship, I really wanted to work in the transmission area, specifically at the submarine cable terminal station in Aldeburgh. I requested a transfer to this work area which was fortunately agreed a few months later. I spent the majority of my career with BT in the transmission area, which has changed beyond all recognition from my early days. Migrating from copper pair, to copper coax, to fibre optic, with signal structures changing from analogue to digital.

The thing I enjoyed most about being at the exchange were the great colleagues who were happy to help me learn and understand what was required to run the exchange. I also enjoyed learning the techniques of faulting and maintenance necessary to keep equipment functioning correctly.

There were also quiet periods when some fun could be had. My colleagues had invented a game called “Roke” where reels of insulating tape were propelled around the exchange by means of a walking stick. At various points on the floor, circles were marked and acted as pockets/holes. The aim was to get your reel into the pocket/hole. There were penalties awarded if you happened to hit a colleague on the ankle (a Fetlock) when it was your turn.

The Exchange Now

"Creative studios, co-working and tech spaces"

The Art Station is an arts organisation and charity supporting the creative industries in coastal East Suffolk by providing affordable creative studios, co-working and tech spaces, and by enabling new creative networks to develop in the region. Having carried out a major refurbishment of the first floor of Saxmundham’s former post office and telephone exchange, this unique venue is now a base for an engaging art and learning programme.

In September 2021, The Art Station opened areas of the former Saxmundham Telephone Exchange to the public for the first time as part of a series of heritage open days. Partnering with BT Adastral Park and Saxmundham Museum, they celebrated the building’s historical significance as a hub for connectivity in Suffolk from the 1950s-1980s.

Former exchange equipment was displayed alongside archival documents, films and photographs to explain the development of technology over the years.

Contemporary artworks by digital artists Henry Driver and Emily Godden were also shown in the space, and local oral historian Belinda Moore interviewed former employees and community members to gather their stories and recollections of the exchange.